Movements Analysis of Preterm Infants by Using Depth Sensor

Computing methodologies → Modeling methodologies; 3D imaging; Eng. Cenci, Prof. Carnielli

ABSTRACT

Qualitative assessment of general movements in preterm infants is widely used in clinical practice. It can enable early detection of neurological dysfunctions and consequent neuromotor impairments in high risk infants. However, the outcome of these assessments is not standardized and it is influenced by examiner’s subjective interpretation. For this reason, there is an increasing interest in the use of automated movement recognition technologies being applied in this field. In this work, we use a video-based system for preterm infant’s movements assessment to provide a 3D motion analysis method able to extract some important indicators from the sequence of depth images collected by using an RGB-D sensor placed over the infant lying on the crib. The advantage of the proposed method is that it is objective, contactless, non-invasive, easy to install, affordable and suitable to be used in an indoor environment with poor lighting, as might be rooms in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, where these infants are taken into care. Experimental results show that the proposed method is able to derive from statistical analysis of depth data some key performance indicators, each of which describes different characteristics of the infant’s spontaneous movements. Preliminary tests are conducted in the experimental phase on a preterm infant hospitalized in a women’s and children’s hospital. The project can be used to investigate the relationship between the characteristics of spontaneous movements and the presence of pathologies as cerebral palsy or other minor neurological dysfunctions.

CCS CONCEPTS

• Computing methodologies → Modeling methodologies; 3D

imaging;

∗Eng. Cenci

†Prof. Carnielli

Permission to make digital or hard copies of all or part of this work for personal or

Permission to make digital or hard copies of all or part of this work for personal or classroom use is granted without fee provided that copies are not made or distributed for profit or commercial advantage and that copies bear this notice and the full citation on the first page. Copyrights for components of this work owned by others than ACM must be honored. Abstracting with credit is permitted. To copy otherwise, or republish, to post on servers or to redistribute to lists, requires prior specific permission and/or a fee. Request permissions from permissions@acm.org. IML ’17, October 17-18, 2017, Liverpool, United Kingdom © 2017 Association for Computing Machinery. ACM ISBN 978-1-4503-5243-7/17/10. . . $15.00 https://doi.org/10.1145/3109761.3109773

KEYWORDS

Preterm infant’s movement analysis, 3D Tracking, Clustering, Modelling

ACM Reference format:

Annalisa Cenci, Daniele Liciotti, Emanuele Frontoni, Primo Zingaretti,and Virgilio Paolo Carnielli. 2017. Movements Analysis of Preterm Infants

by Using Depth Sensor. In Proceedings of IML ’17, Liverpool, United Kingdom,

October 17-18, 2017, 9 pages.

https://doi.org/10.1145/3109761.3109773

1. INTRODUCTION

Every year there are more than 15 million worldwide preterm births and the number of cases continues to rise [28]. Preterm infants are babies born between the 22nd and 36th week of gestation that often have health problems because of preterm birth affects the anatomical and functional development of all organs, inversely with gestational age. One of the biggest problems concerns the functional integrity of the neonate’s central nervous system (CNS). Preterm infants, in fact, are at higher risk of developing adverse neurodevelopmental outcomes and correlated motor impairments than infants born at term [27]. Cerebral palsy (CP) is a permanent disorder in the development of movement and posture and is one of the major disabilities that affects up to 18% of infants who are born extremely preterm [23]. The total rate of neurological impairments, developmental delays and other motor coordination disorders due to less severe category of minor neurological dysfunctions is up to 45% [14]. For the moment, there are no standardized clinical guidelines to assess the risk of later disabilities and predict motor impairment in high risk infants. Neuroimaging results, such as MRI and clinical neurological examination, integrated with infant’s clinical history, are used to identify infants at highest risk through different clinical assessments and experience of healthcare professionals. These sophisticated brain imaging techniques can provide additional information for conditions like CP [22], but these approaches are not yet suited for early diagnosis. CP diagnosis generally cannot be made definitively until a child is at least 3-4 years-old [23]. However, in order to limit the consequences of CP or other minor neurological dysfunctions, physiotherapy should start as soon as possible, meaning that infants at risk have to be identified from the earliest possible age. Though the major injury cannot be completely repaired, with an early identification follow-ups after discharge can be planned in a more focused way in order to provide specific interventions and information for parents about infant’s prognosis. In last years, it was found that the spontaneous motility of preterm infants during their first weeks of life has an important clinical significance. The study of the early motor repertoire in preterm infants is an important predictor of nervous system dysfunctions and neuromotor impairments in high risk infants [4] and it can be considered as an essential step to optimise therapeutic approaches [5]. Prechtl proposed a new method to study infant nervous system by evaluating the quality of movement patterns in infants. In [10], authors introduced the term General Movements (GMs) to describe whole-body movements that have varying speed, amplitude and sequence and in [9] they developed a qualitative approach to assess infants’ motor integrity based on the observation of spontaneous motor movements. GMs can be observed in newborns and young infants until the 20th week post term. In preterm infants (until the 4 th week post term) GMs are called Writhing Movements (WMs); they seem to be more proximal and have small to moderate amplitude and slow to moderate speed. To the 6 th -8 th week post term GMs are called Fidgety Movements (FMs); they appear more distal, circular, with a moderate speed, a smaller amplitude, a constant fluency and are characterized by variable limbs acceleration in all directions. The transition from WMs to FMs indicates a changing maturational stage, whereas the absence of FMs in infants at the 9 th -20th week post term is proved to be a marker for later disability and CP [2]. Also the presence of the cramped synchronized general movements (CSGMs), in which infant’s limbs are rigid and move almost simultaneously during preterm and term age, have high predictive value for CP development, if observed persistently during a certain number of weeks [12]. The quality of GMs is evaluated by trained observers meaning that GMs assessment (GMA) is based on visual observation by physicians and, thereby, that the outcome measures are not standardized and influenced by examiner’s subjective interpretation. The GMA technique is time-consuming, depends on examiner’s experience and shows a considerable intra and inter-observer variability [3]. For these reasons, an objective (observer-independent) method, that automates the process of assessing the quality of infant GMs, would be preferable. Computer-based analysis of GMs could be a useful tool to support the physician in his medical decisions. Nowadays, the advanced motion capture technologies have made possible the quantitative analysis of movement and the classification of “normal” and “at risk” movements based on objective criteria. However, the utility of these methods is often limited by the need for complex equipment and instrumentation for advanced analyses and for highly experienced personnel who is required [26]. Instead, an ideal system for analysing infants movements in a clinical environment, as might be the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU) where we tested our solution, has to provide the following characteristics: the system has to be cheap, easy to install, noninvasive and user-friendly and has to provide in outcome objective, accurate and reliable measures.

1.1 Contributions of this paper

In this work, we describe our contribution for preterm infant’s movements analysis, by providing a low-cost video-based system that achieves all previous requirements by using a depth sensor positioned above the infant lying on the infant warmer. The advantage of the proposed method is that it is contactless, non-invasive, easy to install and suitable to be used in an indoor environment with poor lighting, as might be rooms in the NICU. Our aim is to provide a 3D motion analysis system that is able to extract some important features from the sequence of depth images collected by RGB-D sensor, which serve as quantitative and qualitative indicators of infant’s movements. These indicators can be used to objectively and quantitatively study infant’s movements during his development. In that way, it will be possible to see the change of movements type during the time, the transition from WMs to FMs, the absence of FMs or the presence of abnormalities in movement as CSGMs, the improvements after physiotherapy. The paper is mainly focused on the statistical method reporting only preliminary test results conducted in the experimental phase on a preterm infant hospitalized in the NICU of the Women’s and Children’s Hospital “G.Salesi” in Ancona (Italy). The goal is to extract a set of parameters from statistical analysis of depth data, collected from the RGB-D sensor of the video-based system installed over the crib, which support clinician in quantifying movements, e.g. with information about movements percentage, velocity, acceleration and activity sequences. The project opens also to future evolutions in the direction of infants’ classification in “healthy” and “at risk” classes. The paper is organized as follows: next section (section 2) describes related works and the state-of-the-art in the field of automated infant’s movement recognition; section 3 presents the proposed method for preterm infant’s movements analysis by using a depth sensor; section 4 presents results and discussion followed by conclusion and future works in section 5.

2. STATE OF THE ART

The clinical importance of the early detection of neuromotor impairments in high risk infants has led to an increasing interest in the use of automated movement recognition technologies being applied in this field. Over last years, several researchers tried to overcome GMA subjectivity by attempting to automatically analyse GMs. Different methods of data acquisition (e.g. optical or magnetic tracking, acceleration measurements, image processing) have been studied. However, these approaches are often based on complex equipment and used methods are not always suitable for a clinical environment. In [25] automated movement recognition for clinical movement assessment in high risk infants are divided in two main categories: video-based assessment and assessment through direct movement sensing. Video-based movement assessment systems can be divided into three-dimensional (3D) motion capture systems, based on special markers that should be attached to the limbs being tracked, and systems that use traditional colour (RGB) sensors. A first 3D motion capture approach was performed by Meinecke et al. in [26]. Based on a 3D motion analysis system, the aim of this study is to develop a methodology in the direction of an objective and quantitative description of GMs of infants within the first month of life. The measurement procedure allows the spatial detection and quantification of full body movements for long-term control with very high 3D tracking accuracy and resolution (both spatial and temporal), but at a considerable price and setup effort. With a similar setup, in [18, 19] Kanemaru and colleagues analysed infants’ GMs in order to investigate the relationship between the jerkiness in spontaneous movements at term age and the development of CP at 3 years of age. However, 3D motion analysis of the whole body is a demanding task, especially in the case of very small infants. Infant’s movements must not be impeded by cumbersome measurement setups, because the aim is to provide the basis for the application of quantitative methods in clinical routine. Systems that use standard video cameras, e.g. webcams and RGB sensors, are also used for markerless infants’ motion capture. These systems are a more affordable alternative to 3D motion capture systems and require a less set up effort, allowing their applications in research and clinical settings. However, these approaches have lower spatial and temporal resolution and less accurate tracking than 3D motion systems, which limit the level of analysis detail . Adde and co-workers used a video-based analysis system for quantitative and qualitative assessments of infants’ GMs [1]. They developed the General Movement Toolbox (GMT) by modifying some modules of the Musical Gesture Toolbox (MGT), a software collection for performing video analysis of music-related movements in musicians and dancers [17]. By using the so called “motiongrams” for quantifying changes in the infant’s movements, the GMT is able to detect FMs as described in the GMA. More recent studies have successfully applied accelerometers to preterm infants to measure spontaneous movements [15, 20]. In [11] authors tested the use of wireless accelerometers in an NICU and compared accelerometers data to the GMA in order to investigate whether accelerometery, combined with machine learning techniques, could accurately identify CSGMs. As in the case of traditional cameras, the use of accelerometers provides low spatial resolution, occasional data losses and relative movement capture only. In [21] authors used another approach in the movement sensing assessment class by tracking body segments of upper and lower limbs during GMs with a magnetic tracking system compared with traditional GMA through video analyses. Despite the increasing popularity of depth sensors, these have not yet been used extensively for movement analysis in infants. This contrasts with other clinical applications, e.g. gait analysis [13], rehabilitation monitoring [7], postural control assessment [8], or monitoring of musculoskeletal disorders [30]. Although its great potential in general movement analysis, depth sensors use is not largely explored with regards to preterm infants’ GMA. This may have happened because the provided body tracking functionality of Kinect sensor does not work reliably for humans smaller than one meter, which makes it unsuitable for tracking infants. In [16] authors started to develop a 3D motion analysis system based on the use of Kinect sensor by providing the development of a markerless body pose estimator in single depth images for infants as the first step towards this goal. The advantages of this kind of solution is that the use of depth sensors provides high spatial resolution with a markerless, noninvasive, low-cost and privacy preserving motion capture unlike 3D motion capture studied until now. For these reasons, we focus our attention on this approach by continuing the work started in [6]

3. THE PROPOSED METHOD

In this section we describe a method that uses a video-based system developed in our previous work [6]. In particular, subsection 3.1 explains the main steps of data acquisition and subsection 3.2 describes the processing method. Subsection 3.3 defines the main parameters that we use for the analysis in the results (section 4).

3.1 Data acquisition

The system hardware architecture consists of an RGB-D sensor placed perpendicularly above the infant, lying in a supine position on the crib, at a distance of 70 cm, normally directed to the subject. The entire sensor is composed by an RGB sensor and an infrared sensor, that provides depth map. In the previous work, we developed an acquisition framework, based on vision techniques, which can detect infant’s movements in real time. The main tasks of this framework are:

• frame acquisition;

• noise filtering;

• infant’s segmentation;

• motion analysis

As output, we obtain a list of blobs that represent the variations of the depth values due to infant’s movements. These regions are identified and filtered depending on the area. The algorithm in detail is available in [6]. We customise this framework in order to permit extraction and exportation of depth values and timestamps related to movement blobs.

3.2 Data processing

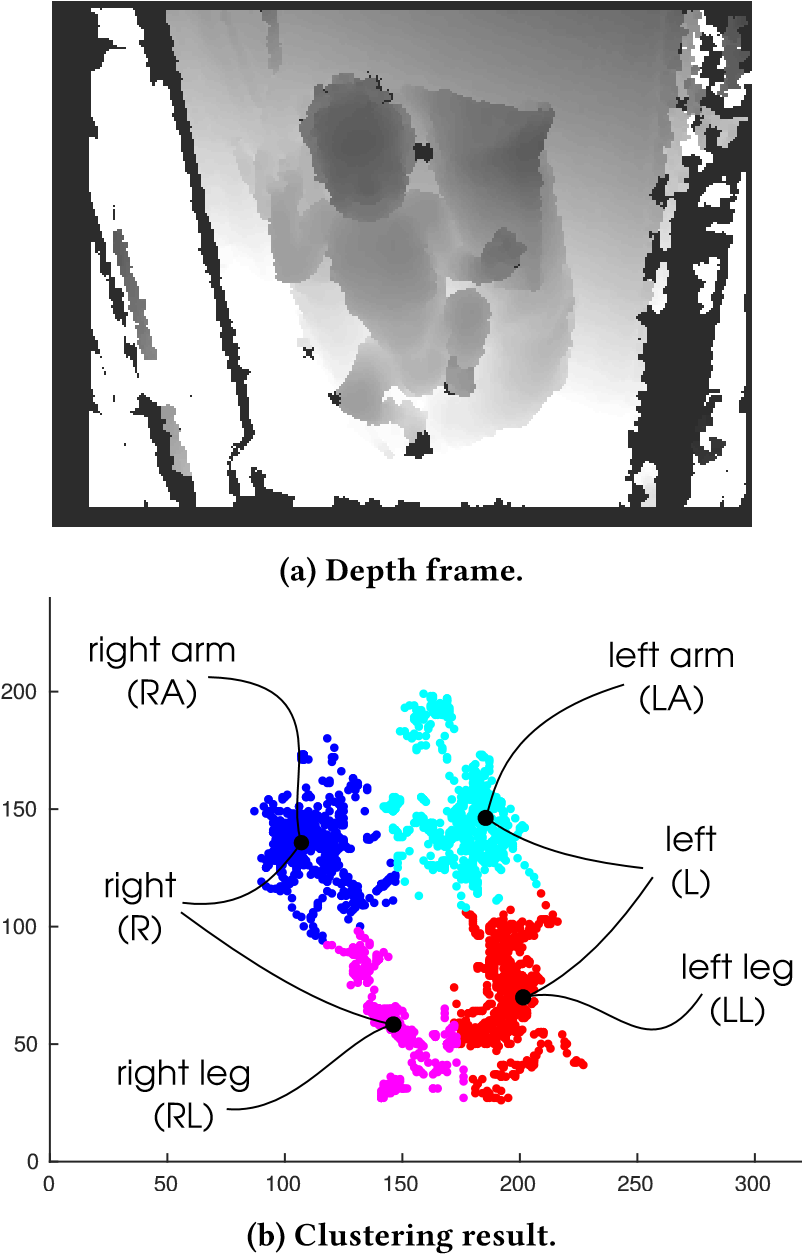

After a preliminary analysis, we plot the coordinates of the various instances of the movement blobs (x,y) and we can observe that points are distributed in 4 well separated clusters; therefore, we can use K-means algorithm as a clustering method, setting k equal to 4, i.e. the number of the limbs being tracked. K-means clustering [24] is a commonly used method to automatically partition a dataset into k groups. It proceeds by selecting k initial cluster centres and then iteratively refining them as follows: (1) Each instance di is assigned to its closest cluster centre. (2) Each cluster centre Cj is updated to be the mean of its constituent instances. The algorithm converges when there is no further change in assignment of instances to clusters.

K-means clustering provides in output a ground truth vector that associates to each blob instance (i.e. to each blob timestamp) the cluster value assigned to the corresponding limb:

- right leg (RL);

- left leg (LL);

- right arm (RA);

- left arm (LA);

as shown in figure 1. Considering that each timestamp instance can be associated to multiple clusters because limbs can move simultaneously, we use this ground truth vector as the input of an algorithm that generates the states vector. Each limb can assume two different states, “in movement” or “not in movement”, and, therefore, considering 4 limbs, the number of possible combinations is equal to 2 4 = 16. At the end of the algorithm we have in output the states vector that associates to each timestamp of the recorded video session a state giving information about which limbs are “in movement” in that moment (timestamp). States vector elements value can range from 1 to 16 as shown in figure 2. Since we have a temporal sequence of 16 possible combinations (states) in which the infant can be in, we can model infant’s movements sequence as a series of transitions states by using Markov Chain (MC). MC is a natural formalism for modelling users’ behaviours and it is widely used in many applications. In this paper, we model the experiment results with a MC, in particular using a transition matrix, in which the probabilities that infant changes his state are recorded. For example, the transition from state 1 to state 2 records the percentage of occurrences that infant has passed from state 1 to state 2. We formalise our MC model for measuring the movements change in a preterm infant’s GMA between the rounds of the experiment under consideration. A MC is defined as M = (S, P) and consists of states, i, in a finite set S of size n, and an n − by − n transition matrix:

P = {pij |i, j ∈ S}

The transition matrix P is row stochastic, i.e. for all states,i, Í j pij = 1, and we assume that P is irreducible and aperiodic, i.e. that exists m such that P m > 0.

3.3 Parameter extraction

Using these preprocessed data and movement blobs position data, we derive the following 10 Key Performance Indicators (KPIs), each of which describes different characteristics of the infant’s spontaneous movements. M l % = Í i t l i ttot (1) where t l i are the time instants during which the l limb (RL, LL, RA, LA) is moving. Ml % is the percentage of the movement of each limb. M G % = Í l Í i t l i ttot (2) is the general movement percentage of all the limbs over the time of a recording session ttot . M s % = Í i t s i ttot (3) where t s i are the time instants during which the s state (from 1 to 16) is active. Ms % is the percentage of movement of each state over the time of a recording session ttot . M α % = Í i t l i ttot α ∈ {L, R},l ∈ α (4) is the percentage of the movements of each body part, where α indicates, respectively, the right side (R) and the left side (L) of infant’s body. t l = Í i t l i n l (5) where n l indicates the number of movement blobs belonging to the same l limb, which corresponds to the number of times l limb moves. t l is the average time of movement of each limb expressed in seconds. t s = Í i t s i n s

where n s indicates the number of movement blobs belonging to the same s state, which corresponds to the number of times states are active. t s is the average time of movement of each state expressed in seconds. t α = Í i t l i n α α ∈ {L, R},l ∈ α (7) where n α indicates the number of movement blobs belonging to α body side, which corresponds to the number of times α body side moves. t α is the average time of movement of each body side expressed in seconds. v l = Í i dpl i d tl i n l (8) is the average velocity of the movements of each limb calculated on the basis of the position data for the movement blobs of each limb and expressed in cm/s. We calculated 3D tangential velocities dpl i d tl i , where p is the 3D Euclidean distance. Next, we averaged the instantaneous velocities over the number of movement blobs belonging to the same limb, which is referred to as average velocity of each limb. a l = Í i dv l i d tl i n l (9) is the average acceleration of the movements of each limb always calculated on the basis of the position data for the movement blobs of each limb and expressed in cm/s 2 . We averaged instantaneous accelerations, obtained by deriving instantaneous velocities, over the number of movement blobs belonging to the same limb, which is referred to as average acceleration of each limb. V l = 4 3 πr 3 (10) is the estimated 95% spheric volume of each limb expressed in m3 , which corresponds to volume of the 95% bivariate confidence sphere, which is expected to enclose approximately 95% of the 3D points inside each cluster

4. RESULTS

In order to analyse the results of the experiment, we built a dataset described in subsection 4.1. By using this dataset we calculate the 10 KPIs for each recording session showed in table 1, that are discussed in subsection 4.2

4.1 MIA (Motion Infant Analysis) dataset

MIA dataset1 consists in the states vector, along with the corresponding timestamp, derived from depth measurements collected by an RGB-D sensor placed perpendicularly above an infant, lying in a supine position on the crib, at a distance of 70 cm, normally directed to the subject. The preterm infant under examination is a male hospitalized in the NICU of the Women’s and Children’s Hospital “G.Salesi” of Ancona (Italy) of 37 + 1 weeks of gestational age, with a gestational age at birth of 31 + 2 weeks and a weight of 2050д. For data collection we chose the time interval between one meal and the following. During this period, of about 4 hours, the infant can be awake or asleep. We divided this time interval in recording sessions of 300 seconds each one, which allowed us to discard those records in which there is an interaction with a nurse or a clinician. As a result MIA dataset contains a timeline of 16 different states in which the infant under examination was in, for a total period of 35 recording sessions.

4.2 Discussion

Data of table 1 show the presence of three long periods of inactivity, affecting recording sessions 8, 10 − 12, 32 − 33, in which the infant is completely stationary. During the other recording sessions inactivity moments (state 1) alternate with moments during which infant moves one or more limbs (states 2 to 16). These information are also clearly visible in figure 3. Thanks to the MG % KPI we can see that the percentage of total infant’s movement averaged over 35 recording sessions is equal to 34.14%.

In particular, 17.76% is the percentage of movement for RL, 16.91% for LL, 18.05% is the one for RA and 18.67% for LA. The Ml % KPI also highlights that over the 35 recording sessions the upper limbs, RA and LA (red-highlighted), move more than lower limbs, RL and LL (yellow-highlighted). From Mα % KPI we can see that the right side of the body (RL and RA) and the left one (LL and LA) are characterized by approximately the same percentage of movement over the total recordings, i.e., they move on average for the same time. Although on average arms move for the same time, thanks to t l KPI, we can see that LA (t LA = 0, 60 s, red-highlighted) makes longer movements rather than the RA (t RA = 0, 51 s) and also with respect to the legs (t RL = 0, 49 s, t LL = 0, 52 s). This also influences the average duration of the movements of the left part of the body (t L = 0, 97 s, red-highlighted), which is greater than that of the right side (t R = 0, 85 s). v l KPI gives information about movements average velocity; we can see that RL makes jerks and very fast movements (v RL = 21, 44 cm/s, red-highlighted), otherwise RA makes slower movements (v RA = 13.98 cm/s, yellow-highlighted) than other limbs. This is confirmed also by a l KPI, greater for LA and lower for RA (a RL = 100, 71 cm/s 2 , red-highlighted and a RA = 57, 04 cm/s 2 , yellow-highlighted). From V l KPI we can also obtain information about movements amplitude: legs, as we expected, cover larger volumes (red-highlighted) than the arms as they perform larger movements. Figure 3 shows the activation of each state s during the registration period. From this figure it is clear that infant is stationary for most of the time (state 1) and that remains completely stationary for three long periods of time, as already highlighted in table 1. When the infant is moving (states 2 to 16), the state, in which he is in, varies very quickly and for this reason it is difficult to view the state changes in the image. In figure 4, that represents the modelling of the MC transition matrix P of the total recorded period, we can see the matrix representation of the probability of transition from one state to another, whose values range from zero to one. The fact that the probability values along the matrix diagonal are very high means that the probability that in the next instant (K + 1) infant remains in the same state of the previous instant is very high.

In other words, it is very likely that once infant moves certain limbs, he continues moving those same limbs also in the next instant. Furthermore, along the matrix diagonal we can see some element with more intense colour (higher probability) than others, e.g. elements P(2, 2), P(3, 3), P(5, 5), P(9, 9), in which infant moves only one limb, meaning that the probability that he continues to move only the same limb is high. We can see that the highest probability value is the element P(1, 1) because of the infant is stationary for 65, 86% of the total time, and, therefore, the probability that he remains in state 1 is very high. Other elements (not along the diagonal) with significantly higher values are due to the addition in the next state of the movement of a single other limb in addition to those already moved in the previous state. An example of these cases can be seen in element P(4, 8), that describes the probability of a transition from state 4, in which infant moves legs, to state 8, in which he moves legs and RA. We calculate transition matrix for each recording session and then we plot the diagonal element values for each session in figure 5. In this graph, we can find two areas where the probability of remaining on the same state decreases for all the diagonal elements except that one related to the state 1 (which corresponds to infant inactivity). We can see that these areas correspond with recording sessions mentioned before, in which the infant is stationary (8, 10 − 12, 32 − 33). To confirm this, we see that during the recording sessions in which he moves, the probability of all the diagonal elements increases except inactivity probability (state 1), that decreases.

5. CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE WORKS

In this section we describe conclusions and future works. In particular, subsection 5.1 presents the main advantages and disadvantages of the proposed system and subsection 5.2 introduces some possible future developments. In the present work, we propose a novel video-based system for preterm infant’s movements analysis by using a depth sensor placed over the infant lying on the infant warmer. We develop an algorithm able to extract some important features from the sequence of depth images collected by RGB-D sensor. We derive some important indicators that can be used by clinician to objectively study infant’s movements during his development. By using the information included in KPIs it will be possible to quantify the change in infant’s limbs movements during the time and the improvements after physiotherapy, to observe the presence of the physiological transition from WMs to FMs, the absence of FMs or the presence of abnormal movements. From KPIs we can derive information about movements percentage, velocity, acceleration, amplitude and volume, about activities sequences and symmetries in movement. E.g., Ms % KPI, when s = 16, tells us about the percentage time during which the infant moves all the limbs simultaneously and it can give us information about the presence of abnormal movements as CSGMs.

5.1 Advantages and limitations

The proposed system is low-cost and easy to install in the hospital environment where we carried out the experimental phase and where it could be used in the future. It consists of two main components: an RGB-D sensor that does not need external power, since the power supply is provided by the USB port, and a Single Board Computer sufficiently small, but suited to manage all algorithms as specified in [6]. Moreover, it is not bulky or cumbersome as 3D motion capture technologies [26]. Affordability, installability and practicability are important characteristics required to all new systems installed in the NICU. Furthermore, the system is non-contact and non-invasive. This ensures the decrease of the discomfort procured to the baby, reducing the number of transducers applied on the infant skin and also the risk incurred whenever the child comes into contact with external objects, as is the case of marker-based motion capture systems [18, 19, 26] and sensor-based approaches [11, 15, 20, 29]. This aspect is of major importance especially in our case, in which infants have a very small accessible body surface area and a very sensitive skin. Another advantage of the proposed solution is that the use of depth data makes the system suitable to be used in an indoor environment with poor lighting, as might be rooms in the NICU and it allows the preservation of privacy, unlike RGB cameras used in [1, 2, 9]. Limitations of the proposed system are due to occlusions caused by external interventions that occur when nurses or physicians put their hands between the depth sensor and the infant to perform their activities. Another problem may be caused when nurses or clinicians change the position of the infant inside the crib. Such new arrangements may adversely affect clustering goodness. To avoid these issues, we considered only recording sessions in which there are not interactions with nurses or clinicians.

5.2 Further developments

The paper is mainly focused on the statistical method reporting only preliminary test results, but, currently, more extensive studies with more infants are in process. The project, indeed, opens to future evolutions in the direction of infants’ classification in “healthy” and “at risk” classes. Based on this set of parameters, we plan to develop scores to resemble GMA as a support for clinician in CP diagnosis, in order to increase the number of early detections of movement disorders, so that treatment can be started as soon as possible. Another future work involves the use of more advanced computer vision techniques, e.g. DNN, to extract preterm infant’s silhouette from depth frame in order to improve the quality of limbs tracking. Other future developments may involve the use of new, more performing, structured-light sensors, such as our, or of time-offlight (ToF) sensors that supply depth images of better quality and are less affected by the presence of sunlight.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the healthcare personnel of the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (Università Politecnica delle Marche, Ancona, Italy) for his precious collaboration and the continuous support to the work.

REFERENCES

[1] Lars Adde, Jorunn L Helbostad, Alexander Refsum Jensenius, Gunnar Taraldsen, and Ragnhild Støen. 2009. Using computer-based video analysis in the study of fidgety movements. Early human development 85, 9 (2009), 541–547.

[2] Lars Adde, Marite Rygg, Kristin Lossius, Gunn Kristin Øberg, and Ragnhild Støen. 2007. General movement assessment: predicting cerebral palsy in clinical practise. Early human development 83, 1 (2007), 13–18.

[3] I Bernhardt, M Marbacher, R Hilfiker, and L Radlinger. 2011. Inter-and intraobserver agreement of Prechtl’s method on the qualitative assessment of general movements in preterm, term and young infants. Early human development 87, 9 (2011), 633–639.

[4] Marlette Burger and Quinette A Louw. 2009. The predictive validity of general movements–a systematic review. European journal of paediatric neurology 13, 5 (2009), 408–420.

[5] Emma C Cameron, Valerie Maehle, and Jane Reid. 2005. The effects of an early physical therapy intervention for very preterm, very low birth weight infants: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Pediatric Physical Therapy 17, 2 (2005), 107–119.

[6] Annalisa Cenci, Daniele Liciotti, Emanuele Frontoni, Adriano Mancini, and Primo Zingaretti. 2015. Non-Contact Monitoring of Preterm Infants Using RGBD Camera. In ASME 2015 International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference. American Society of Mechanical Engineers, V009T07A003–V009T07A003.

[7] Chien-Yen Chang, Belinda Lange, Mi Zhang, Sebastian Koenig, Phil Requejo, Noom Somboon, Alexander A Sawchuk, and Albert A Rizzo. 2012. Towards pervasive physical rehabilitation using Microsoft Kinect. In Pervasive Computing Technologies for Healthcare (PervasiveHealth), 2012 6th International Conference on. IEEE, 159–162.

[8] Ross A Clark, Yong-Hao Pua, Karine Fortin, Callan Ritchie, Kate E Webster, Linda Denehy, and Adam L Bryant. 2012. Validity of the Microsoft Kinect for assessment of postural control. Gait & posture 36, 3 (2012), 372–377.

[9] Christa Einspieler and Heinz FR Prechtl. 2005. Prechtl’s assessment of general movements: a diagnostic tool for the functional assessment of the young nervous system. Mental retardation and developmental disabilities research reviews 11, 1 (2005), 61–67.

[10] Christa Einspieler, Heinz FR Prechtl, Fabrizio Ferrari, Giovanni Cioni, and Arend F Bos. 1997. The qualitative assessment of general movements in preterm, term and young infants—review of the methodology. Early human development 50, 1 (1997), 47–60.

[11] Mingming Fan, Dana Gravem, Dan M Cooper, and Donald J Patterson. 2012. Augmenting gesture recognition with erlang-cox models to identify neurological disorders in premature babies. In Proceedings of the 2012 ACM Conference on Ubiquitous Computing. ACM, 411–420.

[12] Fabrizio Ferrari, Giovanni Cioni, Christa Einspieler, M Federica Roversi, Arend F Bos, Paola B Paolicelli, Andrea Ranzi, and Heinz FR Prechtl. 2002. Cramped synchronized general movements in preterm infants as an early marker for cerebral palsy. Archives of pediatrics & adolescent medicine 156, 5 (2002), 460– 467.

[13] Moshe Gabel, Ran Gilad-Bachrach, Erin Renshaw, and Assaf Schuster. 2012. Full body gait analysis with Kinect. In Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBC), 2012 Annual International Conference of the IEEE. IEEE, 1964–1967.

[14] MIJNA HADDERS-ALGRA, Kirsten R Heineman, Arend F Bos, and Karin J Middelburg. 2010. The assessment of minor neurological dysfunction in infancy using the Touwen Infant Neurological Examination: strengths and limitations. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 52, 1 (2010), 87–92.

[15] Franziska Heinze, Katharina Hesels, Nico Breitbach-Faller, Thomas Schmitz-Rode, and Catherine Disselhorst-Klug. 2010. Movement analysis by accelerometry of newborns and infants for the early detection of movement disorders due to infantile cerebral palsy. Medical & biological engineering & computing 48, 8 (2010), 765–772.

[16] Nikolas Hesse, Gregor Stachowiak, Timo Breuer, and Michael Arens. 2015. Estimating body pose of infants in depth images using random ferns. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision Workshops. 35–43.

[17] Alexander Refsum Jensenius, Rolf Inge Godøy, and Marcelo M Wanderley. 2005. Developing tools for studying musical gestures within the Max/MSP/Jitter environment. (2005).

[18] Nao Kanemaru, Hama Watanabe, Hideki Kihara, Hisako Nakano, Tomohiko Nakamura, Junji Nakano, Gentaro Taga, and Yukuo Konishi. 2014. Jerky spontaneous movements at term age in preterm infants who later developed cerebral palsy. Early human development 90, 8 (2014), 387–392.

[19] Nao Kanemaru, Hama Watanabe, Hideki Kihara, Hisako Nakano, Rieko Takaya, Tomohiko Nakamura, Junji Nakano, Gentaro Taga, and Yukuo Konishi. 2013. Specific characteristics of spontaneous movements in preterm infants at term age are associated with developmental delays at age 3 years. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 55, 8 (2013), 713–721.

[20] Dominik Karch, Keun-Sun Kang, Katarzyna Wochner, Heike Philippi, Mijna Hadders-Algra, Joachim Pietz, and Hartmut Dickhaus. 2012. Kinematic assessment of stereotypy in spontaneous movements in infants. Gait & posture 36, 2 (2012), 307–311.

[21] Dominik Karch, Keun-Sun Kim, Katarzyna Wochner, Joachim Pietz, Hartmut Dickhaus, and Heike Philippi. 2008. Quantification of the segmental kinematics of spontaneous infant movements. Journal of biomechanics 41, 13 (2008), 2860– 2867.

[22] Steven J Korzeniewski, Gretchen Birbeck, Mark C DeLano, Michael J Potchen, and Nigel Paneth. 2008. A systematic review of neuroimaging for cerebral palsy. Journal of child neurology 23, 2 (2008), 216–227.

[23] Ingeborg Krägeloh-Mann and Christine Cans. 2009. Cerebral palsy update. Brain and development 31, 7 (2009), 537–544.

[24] James MacQueen et al. 1967. Some methods for classification and analysis of multivariate observations. In Proceedings of the fifth Berkeley symposium on mathematical statistics and probability, Vol. 1. Oakland, CA, USA., 281–297.

[25] Claire Marcroft, Aftab Khan, Nicholas D Embleton, Michael Trenell, and Thomas Plötz. 2015. Movement recognition technology as a method of assessing spontaneous general movements in high risk infants. Front. Neurol 5 (2015), 22–30.

[26] L Meinecke, N Breitbach-Faller, C Bartz, R Damen, G Rau, and C DisselhorstKlug. 2006. Movement analysis in the early detection of newborns at risk for developing spasticity due to infantile cerebral palsy. Human movement science 25, 2 (2006), 125–144.

[27] David Edward Odd, Raghu Lingam, Alan Emond, and Andrew Whitelaw. 2013. Movement outcomes of infants born moderate and late preterm. Acta pædiatrica 102, 9 (2013), 876–882.

[28] World Health Organization et al. 2012. Born too soon: the global action report on preterm birth. (2012).

[29] Heike Philippi, Dominik Karch, Keun-Sun Kang, Katarzyna Wochner, Joachim Pietz, Hartmut Dickhaus, and Mijna Hadders-Algra. 2014. Computer-based analysis of general movements reveals stereotypies predicting cerebral palsy. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology 56, 10 (2014), 960–967.

[30] Ruizhe Wang, Gérard Medioni, Carolee Winstein, and Cesar Blanco. 2013. Home monitoring musculo-skeletal disorders with a single 3d sensor. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Workshops. 521–528.